Let’s pretend for a moment that you are a giraffe.

You live on the grasslands of the African savanna. You have a neck that is 7 feet long (2.1 meters). Every now and then, you spot a group of humans driving around on a safari taking pictures of you.

But it’s not just your neck and their cameras that separates you from the humans. Perhaps the biggest difference between you and your giraffe friends and the humans taking your picture is that nearly every decision you make provides an immediate benefit to your life.

- When you are hungry, you walk over and munch on a tree.

- When a storm rolls across the plains, you take shelter under the brush.

- When you spot a lion stalking you and your friends, you run away.

On any given day, most of your choices as a giraffe—like what to eat or where to sleep or when to avoid a predator—make an immediate impact on your life.You are constantly focused on the present or the very near future. You live in what scientists call an immediate-return environment because your actions instantly deliver clear and immediate outcomes.

The Delayed Return Environment

Now, let’s flip the script and pretend you are one of the humans vacationing on safari. Unlike the giraffe, humans live in what researchers call a Delayed Return Environment. 1

Most of the choices you make today will not benefit you immediately. If you do a good job at work today, you’ll get a paycheck in a few weeks. If you save money now, you’ll have enough for retirement later. Many aspects of modern society are designed to delay rewards until some point in the future.

This is true of our problems as well. While a giraffe is worried about immediate problems like avoiding lions and seeking shelter from a storm, many of the problems humans worry about are problems of the future.

For example, while bouncing around the savanna in your Jeep, you might think, “This safari has been a lot of fun. It would be cool to work as a park ranger and see giraffes every day. Speaking of work, is it time for a career change? Am I really doing the work I was meant to do? Should I change jobs?”

Unfortunately, living in a Delayed Return Environment tends to lead to chronic stress and anxiety for humans. Why? Because your brain wasn’t designed to solve the problems of a Delayed Return Environment.

Before we talk about how to get started, I wanted to let you know I discuss this topic in more depth in my book, Atomic Habits. If you’re interested in this topic (and learning how to build better habits and break bad ones), check it out.

The Evolution of the Human Brain

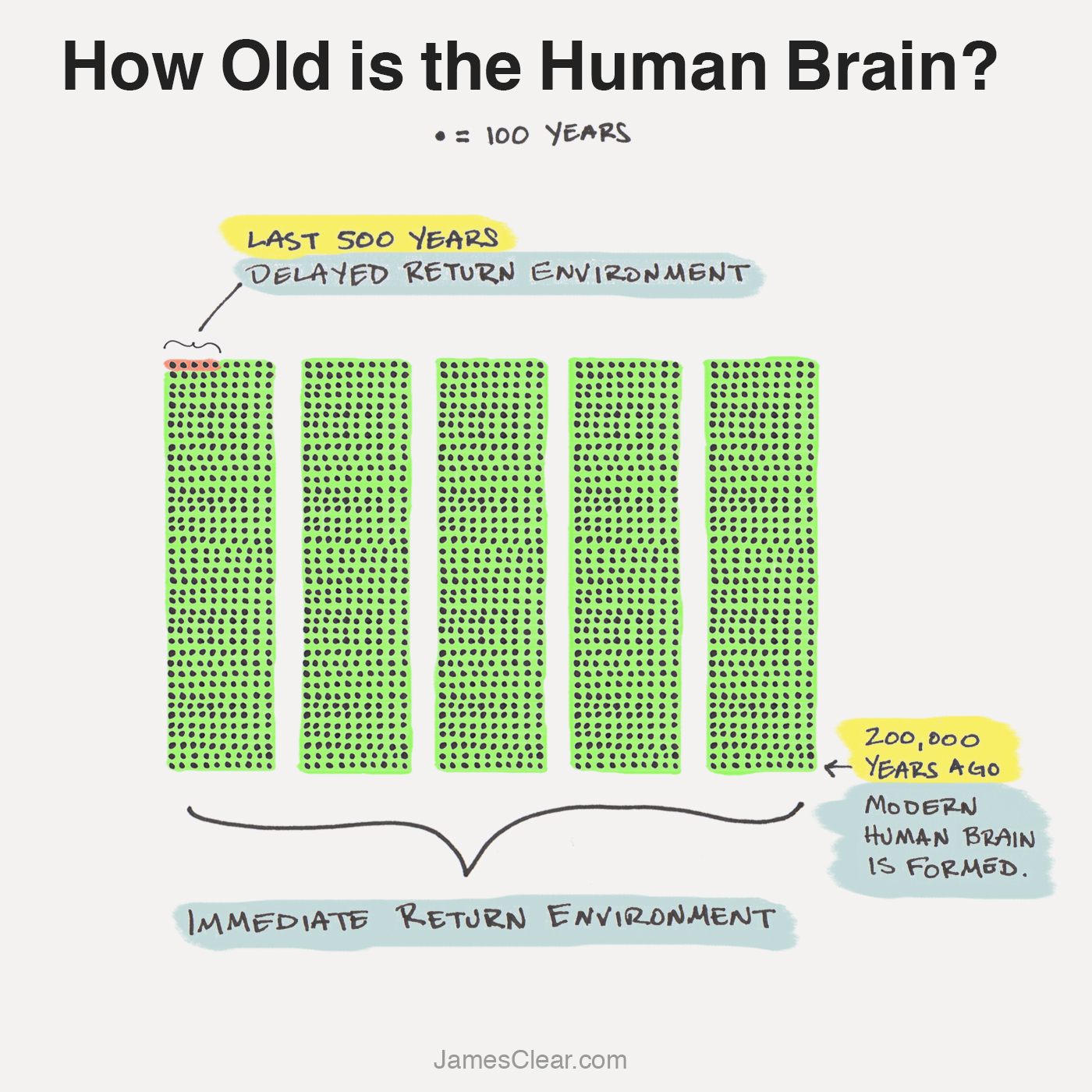

The human brain did not evolve for life in a delayed-return environment.

The earliest remains of modern humans, known as Homo sapiens sapiens, are approximately two hundred thousand years old.2 These were the first humans to have a brain relatively similar to ours. In particular, the neocortex—the newest part of the brain and the region responsible for higher functions like language—was roughly the same size two hundred thousand years ago as today.3 You are walking around with the same hardware as your Paleolithic ancestors.

Compared to the age of the brain, modern society is incredibly new. It is only recently—during the last 500 years or so—that our society has shifted to a predominantly Delayed Return Environment. The pace of change has increased exponentially compared to prehistoric times. In the last 100 years we have seen the rise of the car, the airplane, the television, the personal computer, the Internet, and Beyonce. Nearly everything that makes up your daily life has been created in a very small window of time.

A lot can happen in 100 years. From the perspective of evolution, however, 100 years is nothing. The modern human brain spent hundreds of thousands of years evolving for one type of environment (immediate returns) and in the blink of an eye the entire environment changed (delayed returns). Your brain was designed to value immediate returns. 4

The Evolution of Anxiety

The mismatch between our old brain and our new environment has a significant impact on the amount of chronic stress and anxiety we experience today.

Thousands of years ago, when humans lived in an Immediate Return Environment, stress and anxiety were useful emotions because they helped us take action in the face of immediate problems.

For example:

- A lion appears across the plain > you feel stressed > you run away > your stress is relieved.

- A storm rumbles in the distance > you worry about finding shelter > you find shelter > your anxiety is relieved.

- You haven’t drunk any water today > you feel stressed and dehydrated > you find water > your stress is relieved.

This is how your brain evolved to use worry, anxiety, and stress. Anxiety was an emotion that helped protect humans in an Immediate Return Environment. It was built for solving short-term, acute problems. There was no such thing as chronic stress because there aren’t really chronic problems in an Immediate Return Environment.

Wild animals rarely experience chronic stress. As Duke University professor Mark Leary put it, “A deer may be startled by a loud noise and take off through the forest, but as soon as the threat is gone, the deer immediately calms down and starts grazing. And it doesn’t appear to be tied in knots the way that many people are.” When you live in an Immediate Return Environment, you only have to worry about acute stressors. Once the threat is gone, the anxiety subsides. 5

Today we face different problems. Will I have enough money to pay the bills next month? Will I get the promotion at work or remain stuck in my current job? Will I repair my broken relationship? Problems in a Delayed Return Environment can rarely be solved right now in the present moment. 6

What to Do About It

One of the greatest sources of anxiety in a Delayed Return Environment is the constant uncertainty. There is no guarantee that working hard in school will get you a job. There is no promise that investments will go up in the future. There is no assurance that going on a date will land you a soulmate. Living in a Delayed Return Environment means you are surrounded by uncertainty.

So what can you do? How can you thrive in a Delayed Return Environment that creates so much stress and anxiety?

The first thing you can do is measure something. You can’t know for certain how much money you will have in retirement, but you can remove some uncertainty from the situation by measuring how much you save each month. You can’t be sure that you’ll get a job after graduation, but you can track how often you reach out to companies about internships. You can’t predict when you find love, but you can pay attention to how many times you introduce yourself to someone new.

The act of measurement takes an unknown quantity and makes it known. When you measure something, you immediately become more certain about the situation. Measurement won’t magically solve your problems, but it will clarify the situation, pull you out of the black box of worry and uncertainty, and help you get a grip on what is actually happening.

Furthermore, one of the most important distinctions between an Immediate Return Environment and a Delayed Return Environment is rapid feedback. Animals are constantly getting feedback about the things that cause them stress. As a result, they actually know whether or not they should feel stressed. Without measurement you have no feedback.

If you’re looking for good measurement strategies, I suggest using something simple like The Paper Clip Strategy for tracking repetitive, daily actions and something like The Seinfeld Strategy for tracking long-term behaviors.

Shift Your Worry

The second thing you can do is “shift your worry” from the long-term problem to a daily routine that will solve that problem.

- Instead of worrying about living longer, focus on taking a walk each day.

- Instead of worrying about whether your child will get a college scholarship, focus on how much time they spend studying today.

- Instead of worrying about losing enough weight for the wedding, focus on cooking a healthy dinner tonight.

The key insight that makes this strategy work is making sure your daily routine both rewards you right away (immediate return) and resolves your future problems (delayed return). 7

Here are the three examples from my life:

- Writing. When I publish an article, the quality of my life is noticeably higher. Additionally, I know that if I write consistently, then my business will grow, I will publish books, and I will make enough money to sustain my life. By focusing my attention on writing each day, I increase my well-being (immediate return) while also working toward earning future income (delayed return).

- Lifting. I experienced a huge shift in well-being when I learned to fall in love with exercise. The act of going to the gym brings joy to my life (immediate return) and it also leads to better long-term health (delayed return).

- Reading. Last year, I posted my public reading list and began reading 20 pages per day. Now, I get a sense of accomplishment whenever I do my daily reading (immediate return) and the practice helps me develop into an interesting person (delayed return).

Our brains didn’t evolve in a Delayed Return Environment, but that’s where we find ourselves today. My hope is that by measuring the things that are important to you and shifting your worry to daily practices that pay off in the long-run, you can reduce some of the uncertainty and chronic stress that is inherent in modern society.

I first came across this distinction between Immediate Return Environments and Delayed Return Environments in The Mysteries of Human Behavior by Mark Leary. I found the whole course fascinating and definitely recommend it if you are interested in psychology and human behavior.

Ian Mcdougall, Francis H. Brown, and John G. Fleagle, “Stratigraphic Placement and Age of Modern Humans from Kibish, Ethiopia,” Nature 433, no. 7027 (2005), doi:10.1038/nature03258.

Some research indicates that the size of the human brain reached modern proportions around three hundred thousand years ago. Evolution never stops, of course, and the shape of the structure appears to have continued to evolve in meaningful ways until it reached both modern size and shape sometime between one hundred thousand and thirty-five thousand years ago. Simon Neubauer, Jean-Jacques Hublin, and Philipp Gunz, “The Evolution of Modern Human Brain Shape,” Science Advances 4, no. 1 (2018): eaao5961.

Research has shown that the ability to delay gratification is one of the primary drivers of success. Isn’t it interesting that delaying gratification is both the opposite of what your brain evolved to do and the skill that matches the Delayed Return Environment we live in today? For millions of years, humans survived because we were wired for immediate gratification (eat now, take shelter now, have sex now), but today the opposite strategy helps us achieve “success.” I doubt we will know in my lifetime, but it will be interesting to see if delaying gratification is merely a tactic favored by our current society that will fade away in the long-run or if it is a sustainable long-term pressure that will shift the course of our evolution.

It has been pointed out to me by a few readers that many wild animals do face chronic stress. For example, baboons and other mammals experience stress related to social status and rank within their tribe. I will be reading more about these nuances and, if necessary, I will update my thoughts in a future post.

Even many of the acute problems we face today are very different from the acute problems of Immediate Return Environments. Consider turbulence on an airplane. This is an immediate, short-term problem that makes many travelers feel stressed and anxious. Unlike acute problems in the wild, however, there is nothing you can do about it except sit there. When you saw a lion in the grass, you could at least run. But our environment has changed so much that many of the acute problems we face, we can no longer take action on. We can’t resolve the stress ourselves. We can only sit and worry.

Yet another reason to focus on the system and not the goal.