This article is an excerpt from Atomic Habits, my New York Times bestselling book.

Most people think that building better habits or changing your actions is all about willpower or motivation. But the more I learn, the more I believe that the number one driver of better habits and behavior change is the choice architecture of your environment.

Let me drop some science into this article and show you what I mean…

The Impact of Choice Architecture

Anne Thorndike, a primary care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, had a crazy idea. She believed she could improve the eating habits of thousands of hospital staff and visitors without changing their willpower or motivation in the slightest way.1 In fact, she didn’t plan on talking to them at all.

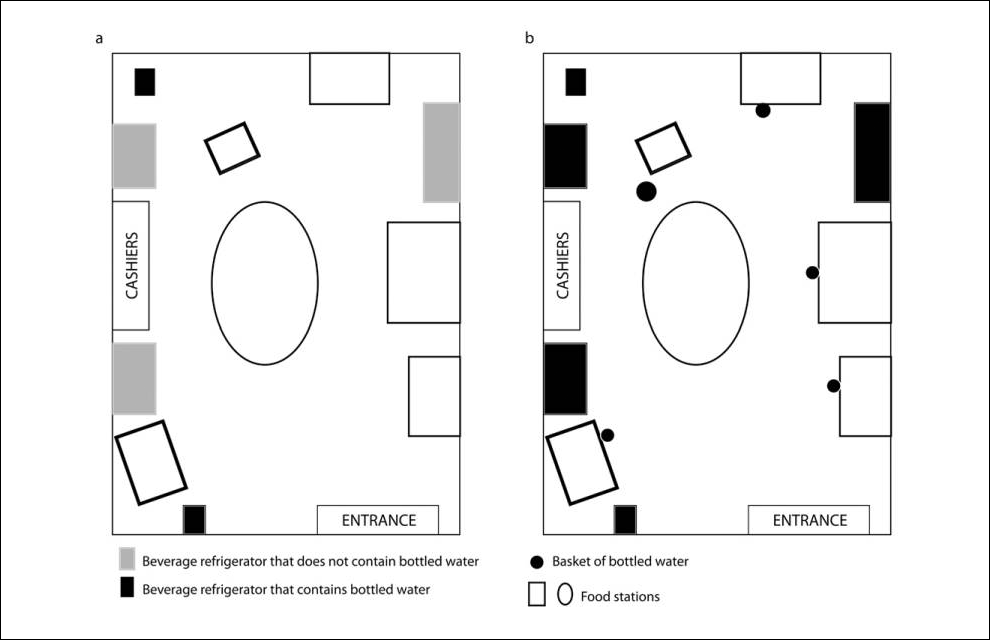

Thorndike and her colleagues designed a six-month study to alter the “choice architecture” of the hospital cafeteria. They started by changing how drinks were arranged in the room. Originally, the refrigerators located next to the cash registers in the cafeteria were filled with only soda. The researchers added water as an option each one. Additionally, they placed baskets of bottled water next to the food stations throughout the room. Soda was still in the primary refrigerators, but water was now available at all drink locations.

The image below depicts what the room looked like before the changes (Figure A) and after the changes (Figure B). The dark boxes indicate areas where bottled water is available.

What happened?

Over the next three months, the number of soda sales at the hospital dropped by 11.4 percent. Meanwhile, sales of bottled water increased by 25.8 percent. They made similar adjustments—and saw similar results—with the food in the cafeteria. Nobody had said a word to anyone eating there.

People often choose products not because of what they are, but because of where they are.2 If I walk into the kitchen and see a plate of cookies on the counter, I’ll pick up half a dozen and start eating, even if I hadn’t been thinking about them beforehand and didn’t necessarily feel hungry. If the communal table at the office is always filled with doughnuts and bagels, it’s going to be hard to not grab one every now and then. Your habits change depending on the room you are in and the cues in front of you.

Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior. Despite our unique personalities, certain behaviors tend to arise again and again under certain environmental conditions. In church, people tend to talk in whispers. On a dark street, people act wary and guarded. In this way, the most common form of change is not internal, but external: we are changed by the world around us. Every habit is context dependent.

To Change Your Behavior, Change Your Environment

Every habit is initiated by a cue, and we are more likely to notice cues that stand out. Unfortunately, the environments where we live and work often make it easy to not do certain actions because there is no obvious cue to trigger the behavior. It’s easy to not practice guitar when it’s tucked away in the closet. It’s easy to not read a book when the bookshelf is in the corner of the guest room. It’s easy to not take your vitamins when they are out of sight in the pantry. When the cues that spark a habit are subtle or hidden, they are easy to ignore.

Thankfully, there is good news in this respect. You don’t have to be the victim of your environment. You can also be the architect of it.

Here are a few ways you can redesign your environment and make the cues for your preferred habits more obvious:

- If you want to remember to take your medication each night, put your pill bottle directly next to the faucet on the bathroom counter.

- If you want to practice guitar more frequently, place your guitar stand in the middle of the living room.

- If you want to remember to send more thank-you notes, keep a stack of stationery on your desk.

- If you want to drink more water, fill up a few water bottles each morning and place them in common locations around the house.

If you want to make a habit a big part of your life, make the cue a big part of your environment. The most persistent behaviors usually have multiple cues. Consider how many different ways a smoker could be prompted to pull out a cigarette: driving in the car, seeing a friend smoke, feeling stressed at work, and so on.

The same strategy can be employed for good habits. By sprinkling triggers throughout your surroundings, you increase the odds that you’ll think about your habit throughout the day. Make sure the best choice is the most obvious one. Making a better decision is easy and natural when the cues for good habits are right in front of you.

Environment design is powerful not only because it influences how we engage with the world but also because we rarely do it. Most people live in a world others have created for them. But you can alter the spaces where you live and work to increase your exposure to positive cues and reduce your exposure to negative ones. Environment design allows you to take back control and become the architect of your life. Be the designer of your world, and not merely the consumer of it.

This article is an excerpt from Chapter 6 of my New York Times bestselling book Atomic Habits. Read more here.

Anne N. Thorndike et al., “A 2-Phase Labeling and Choice Architecture Intervention to Improve Healthy Food and Beverage Choices,” American Journal of Public Health 102, no. 3 (2012), doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300391.

Multiple research studies have shown that the mere sight of food can make us feel hungry even when we don’t have actual physiological hunger. According to one researcher, “dietary behaviors are, in large part, the consequence of automatic responses to contextual food cues.” For more, see D. A. Cohen and S. H. Babey, “Contextual Influences on Eating Behaviours: Heuristic Processing and Dietary Choices,” Obesity Reviews 13, no. 9 (2012), doi:10.1111/j.1467–789x.2012.01001.x; and Andrew J. Hill, Lynn D. Magson, and John E. Blundell, “Hunger and Palatability: Tracking Ratings of Subjective Experience Before, during and after the Consumption of Preferred and Less Preferred Food,” Appetite 5, no. 4 (1984), doi:10.1016/s0195–6663(84)80008–2.