This article is an excerpt from Atomic Habits, my New York Times bestselling book.

In 1955, Disneyland had just opened in Anaheim, California, when a ten-year-old boy walked in and asked for a job. Labor laws were loose back then and the boy managed to land a position selling guidebooks for $0.50 apiece.

Within a year, he had transitioned to Disney’s magic shop, where he learned tricks from the older employees. He experimented with jokes and tried out simple routines on visitors. Soon he discovered that what he loved was not performing magic but performing in general. He set his sights on becoming a comedian.

Beginning in his teenage years, he started performing in little clubs around Los Angeles. The crowds were small and his act was short. He was rarely on stage for more than five minutes. Most of the people in the crowd were too busy drinking or talking with friends to pay attention. One night, he literally delivered his stand-up routine to an empty club.

It wasn’t glamorous work, but there was no doubt he was getting better. His first routines would only last one or two minutes. By high school, his material had expanded to include a five-minute act and, a few years later, a ten-minute show. At nineteen, he was performing weekly for twenty minutes at a time. He had to read three poems during the show just to make the routine long enough, but his skills continued to progress.

He spent another decade experimenting, adjusting, and practicing. He took a job as a television writer and, gradually, he was able to land his own appearances on talk shows. By the mid-1970s, he had worked his way into being a regular guest on The Tonight Show and Saturday Night Live.

Finally, after nearly fifteen years of work, the young man rose to fame. He toured sixty cities in sixty-three days. Then seventy-two cities in eighty days. Then eighty-five cities in ninety days. He had 18,695 people attend one show in Ohio. Another 45,000 tickets were sold for his three-day show in New York. He catapulted to the top of his genre and became one of the most successful comedians of his time.1

His name is Steve Martin.

How to Stay Motivated

I recently finished Steve Martin's wonderful autobiography, Born Standing Up.

Martin’s story offers a fascinating perspective on what it takes to stick with habits for the long run. Comedy is not for the timid. It is hard to imagine a situation that would strike fear into the hearts of more people than performing alone on stage and failing to get a single laugh. And yet Steve Martin faced this fear every week for eighteen years. In his words, “10 years spent learning, 4 years spent refining, and 4 years as a wild success.”

Why is it that some people, like Martin, stick with their habits—whether practicing jokes or drawing cartoons or playing guitar—while most of us struggle to stay motivated? How do we design habits that pull us in rather than ones that fade away? Scientists have been studying this question for many years. While there is still much to learn, one of the most consistent findings is that the way to maintain motivation and achieve peak levels of desire is to work on tasks of “just manageable difficulty.”2

The Goldilocks Rule

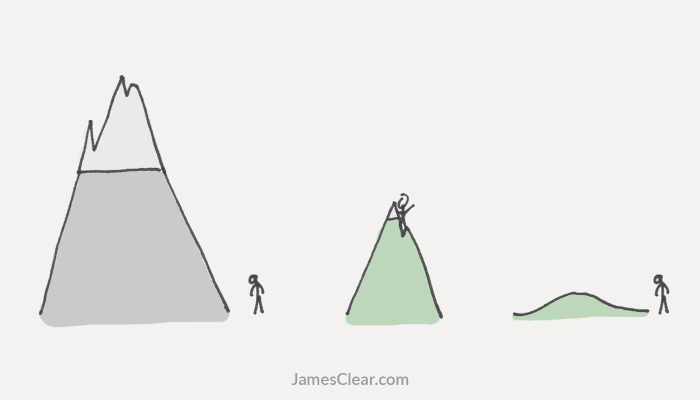

The human brain loves a challenge, but only if it is within an optimal zone of difficulty. If you love tennis and try to play a serious match against a four-year-old, you will quickly become bored. It’s too easy. You’ll win every point. In contrast, if you play a professional tennis player like Roger Federer or Serena Williams, you will quickly lose motivation because the match is too difficult.

Now consider playing tennis against someone who is your equal. As the game progresses, you win a few points and you lose a few. You have a good chance of winning, but only if you really try. Your focus narrows, distractions fade away, and you find yourself fully invested in the task at hand. This is a challenge of just manageable difficulty and it is a prime example of the Goldilocks Rule.

The Goldilocks Rule states that humans experience peak motivation when working on tasks that are right on the edge of their current abilities. Not too hard. Not too easy. Just right.3

Martin’s comedy career is an excellent example of the Goldilocks Rule in practice. Each year, he expanded his comedy routine—but only by a minute or two. He was always adding new material, but he also kept a few jokes that were guaranteed to get laughs. There were just enough victories to keep him motivated and just enough mistakes to keep him working hard.

Measure Your Progress

If you want to learn how to stay motivated to reach your goals, then there is a second piece of the motivation puzzle that is crucial to understand. It has to do with achieving that perfect blend of hard work and happiness.

Working on challenges of an optimal level of difficulty has been found to not only be motivating, but also to be a major source of happiness. As psychologist Gilbert Brim put it, “One of the important sources of human happiness is working on tasks at a suitable level of difficulty, neither too hard nor too easy.”

This blend of happiness and peak performance is sometimes referred to as flow, which is what athletes and performers experience when they are “in the zone.” Flow is the mental state you experience when you are so focused on the task at hand that the rest of the world fades away.

In order to reach this state of peak performance, however, you not only need to work on challenges at the right degree of difficulty, but also measure your immediate progress. As psychologist Jonathan Haidt explains, one of the keys to reaching a flow state is that “you get immediate feedback about how you are doing at each step.”

Seeing yourself make progress in the moment is incredibly motivating. Steve Martin would tell a joke and immediately know if it worked based on the laughter of the crowd. Imagine how addicting it would be to create a roar of laughter. The rush of positive feedback Martin experienced from one great joke would probably be enough to overpower his fears and inspire him to work for weeks.

In other areas of life, measurement looks different but is just as critical for achieving a blend of motivation and happiness. In tennis, you get immediate feedback based on whether or not you win the point. Regardless of how it is measured, the human brain needs some way to visualize our progress if we are to maintain motivation. We need to be able to see our wins.

Two Steps to Motivation

If we want to break down the mystery of how to stay motivated for the long-term, we could simply say:

- Stick to The Goldilocks Rule and work on tasks of just manageable difficulty.

- Measure your progress and receive immediate feedback whenever possible.

Wanting to improve your life is easy. Sticking with it is a different story. If you want to stay motivated for good, then start with a challenge that is just manageable, measure your progress, and repeat the process.

This article is an excerpt from Chapter 19 of my New York Times bestselling book Atomic Habits. Read more here.

Steve Martin, Born Standing Up: A Comic’s Life (Leicester, UK: Charnwood, 2008).

Nicholas Hobbs, “The Psychologist as Administrator,” Journal of Clinical Psychology 15, no. 3 (1959), doi:10.1002/1097–4679(195907)15:33.0.co; 2–4; Gilbert Brim, Ambition: How We Manage Success and Failure throughout Our Lives (Lincoln, NE: IUniverse.com, 2000); Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

For those from different cultures, the Goldilocks Rule is named after the fairy tale of Goldilocks and the Three Bears.