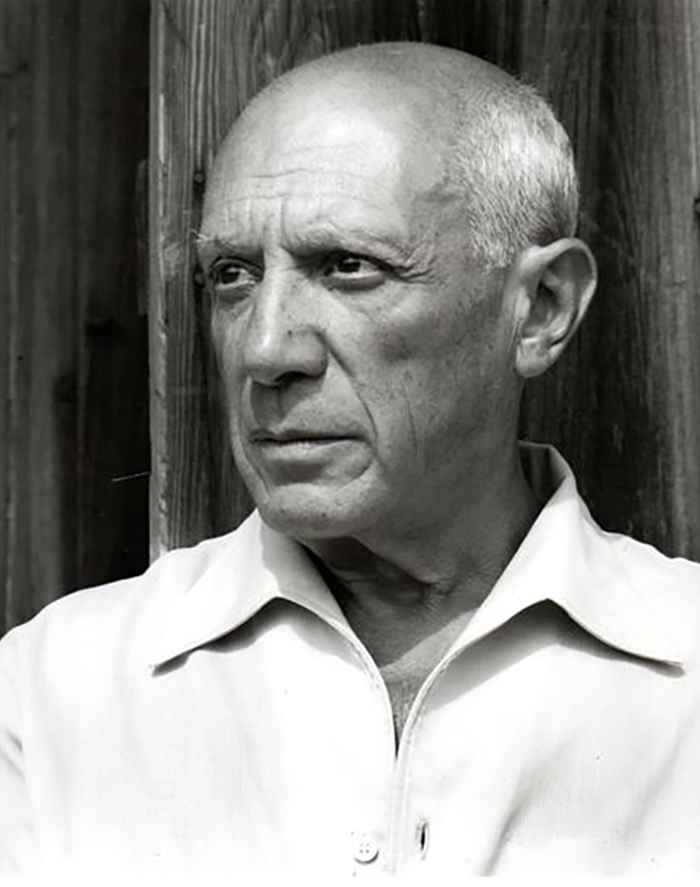

Pablo Picasso. He is one of the most famous artists of the 20th century and a household name even among people who, like myself, consider themselves to be complete novices in the art world.

I recently went to a Picasso exhibition. What impressed me the most was not any individual piece of art, but rather his remarkably prolific output. Researchers have catalogued 26,075 pieces of art created by Picasso and some people believe the total number is closer to 50,000.

When I discovered that Picasso lived to be 91 years old, I decided to do the math. Picasso lived for a total of 33,403 days. With 26,075 published works, that means Picasso averaged 1 new piece of artwork every day of his life from age 20 until his death at age 91. He created something new, every day, for 71 years.

This unfathomable output not only played a large role in Picasso’s international fame, but also enabled him to amass a huge net worth of approximately $500 million by the time of his death in 1973. His work became so famous and so numerous that, according to the Art Loss Register, Picasso is the most stolen artist in history with over 550 works currently missing.

What made Picasso great was not just how much art he produced, but also how he produced it. He co-founded the movement of Cubism and created the style of collage. He was the artist his contemporaries copied. Any discussion of the most well-known artists in history would have to include his name.

Falling in Love With Picasso

Falling in love with Picasso was a terrible thing to do.

His first marriage was to a woman named Olga Khokhlova and they had one child together. The two separated after she discovered that Picasso was having an affair with a seventeen-year-old girl named Marie-Therese Walter. He was 45 years old at the time.

Picasso fathered a child with Walter, but moved on to other lovers a few years later. He began dating an art student named Francoise Gilot in 1944. She was 23 years old. Picasso had just turned 63 at the time.

Gilot and Picasso had two children together, but their relationship ended when Picasso began yet another affair, this time with a woman who was 43 years younger than him. After they separated, Gilot published a book called Life with Picasso, which revealed his long list of sexual flings and sold over one million copies. Out of revenge, Picasso refused to see their two children ever again.

Basically, Picasso’s romantic life was a revolving door of affairs and infidelity. In the words of our guide at the Picasso exhibit, “There were always many others.” There must have been something intoxicating about Picasso because after his death, not one, but two of his lovers committed suicide due to their grief. 1

The Shadow Side

Many of the qualities that make people great have shadow sides as well. Picasso's singular focus on art meant that everything else in life had to take a back seat, including his relationships and his children.

Most humans have a primary relationship with their lover and maintain a variety of hobbies and interests during different periods. Picasso was the reverse. His primary relationship was with his art, while his lovers were like hobbies and passing interests, things he experimented with for a period here and there.

Some scholars believe Picasso's many relationships were essential to the progression of his art. According to art critic Arthur Danto, “Picasso invented a new style each time he fell in love with a new woman.” 2

This was the shadow side of his strength as an artist. The qualities that made Picasso one of the greatest artists of all-time may very well have made him a terrible life partner too. They are like two sides of the same coin. You couldn’t have one without the other. 3

Shadows Appear in All Fields

I don’t mean to pick on Picasso here. The idea that strengths have tradeoffs, especially extreme versions of strengths, holds true in nearly every field.

For example, consider Floyd Mayweather Jr. He is widely considered to be one of the greatest boxers of all-time. His career record is 49-0. He has earned more than $1.3 billion over the course of his career.

He also has serious anger management issues. In 2002, he was charged with two counts of domestic violence. In 2004, two counts of misdemeanor battery against different women. In 2005, another charge of misdemeanor battery. In 2010, yet another misdemeanor battery charge. Not to mention, there have been a number of reported charges that were later dropped.

The qualities that make him a once-in-a-lifetime boxer—his unbridled anger and lack of impulse control—also lead him to be violent in normal situations. This combination makes him unbeatable in the ring and unbearable in the rest of life.

Every Strength Has a Tradeoff

Now, you might be thinking, “Well, you don’t have to cheat on your spouse to produce great art or beat up others to become a good boxer. Those are two different things.”

You’re right. I’m using extreme examples here to make the point, however, it remains true that every strength has a shadow side. Some shadows are darker than others, but all paths to success have a cost.

- Maybe you’re a doctor or a nurse who has learned how to remove yourself from the emotion of death. This quality that allows you to do your job well when patients die each day, but also reduces the empathy and connection you feel with friends and family.

- Maybe you’re a scientist who holds themselves to the highest standards. This perfectionism makes you excellent in the lab, but also leads you to show tough love to your children and they grow up believing nothing they do is ever good enough.

- Maybe you’re a smart and enthusiastic friend who wants to help others by always providing value. You’re just trying to be helpful, but you end up providing too much value. Your friends wish you would just listen to their problems and not feel the need to make your mark on everything.

There are an infinite number of ways this can play out, but one singular punchline: every strength comes with tradeoffs.

Is Success Worth the Shadow Side?

Success is complicated. We love to praise people for becoming famous, for winning championships, and for making tons of money, but we rarely discuss the costs of success.

Did the beauty of Picasso’s art add more joy to the world than the pain he caused through a series of broken relationships? It’s easy for you and me to believe his contribution was net positive because we didn’t have to bear the pain. His ex-wives and mistresses might feel differently—especially the two who committed suicide.

The fact that you cannot escape the downsides of your strengths brings us to an interesting decision point. People often talk about the success they aspire to in life, but as author Mark Manson writes in his popular book, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, the most important question to ask yourself is not, “What kind of success do I want?”, but rather, “What kind of pain do I want?”

Do you want the shadow that comes with the success? Do you want the baggage that comes with the bounty? What kind of pain are you willing to bear in the name of achieving what you want to achieve? Answering this question honestly often leads to more insight about what you really care about than thinking of your dreams and aspirations.

It is easy to want financial independence or the approval of your boss or to look good in front of the mirror. Everybody wants those things. But do you want the shadow side that goes with it? Do you want to spend two extra hours at work each day rather than with your kids? Do you want to put your career ahead of your marriage? Do you want to wake up early and go to the gym when you feel like sleeping in? Different people have different answers and you'll have to decide what is best for you, but pretending that the shadow isn't there is not a good strategy.

Success in one area is often tied to failure in another area, especially at the extreme end of performance. The more extreme the greatness, the longer the shadow it casts.

Success in one area is often tied to failure in another area, especially at the extreme end of performance. The more extreme the greatness, the longer the shadow it casts.

To phrase it differently, the more one dimensional your focus, the more other areas of life suffer. It’s the four burners theory in action. The more you turn up one burner, the more you risk others burning out. The things that make people great in one area often make them miserable in others.

Picasso literally had multiple people killing themselves over losing him. When I was dating, I could barely get someone to text me back.

“Picasso and the Portrait” by Arthur Danto. The Nation 263 (6): 31–35. September 2, 1996.

I also think it is possible, and I’m just theorizing here, that Picasso’s brain was neurologically wired to be more curious than the average person. This curiosity led him to experiment with new forms of art and to produce vibrant work, but also constantly drew him toward new women.