This article is an excerpt from Atomic Habits, my New York Times bestselling book.

In one of my very first articles, I discussed a concept called identity-based habits.

The basic idea is that the beliefs you have about yourself can drive your long-term behavior. Maybe you can trick yourself into going to the gym or eating healthy once or twice, but if you don't shift your underlying identity, then it's hard to stick with long-term changes.

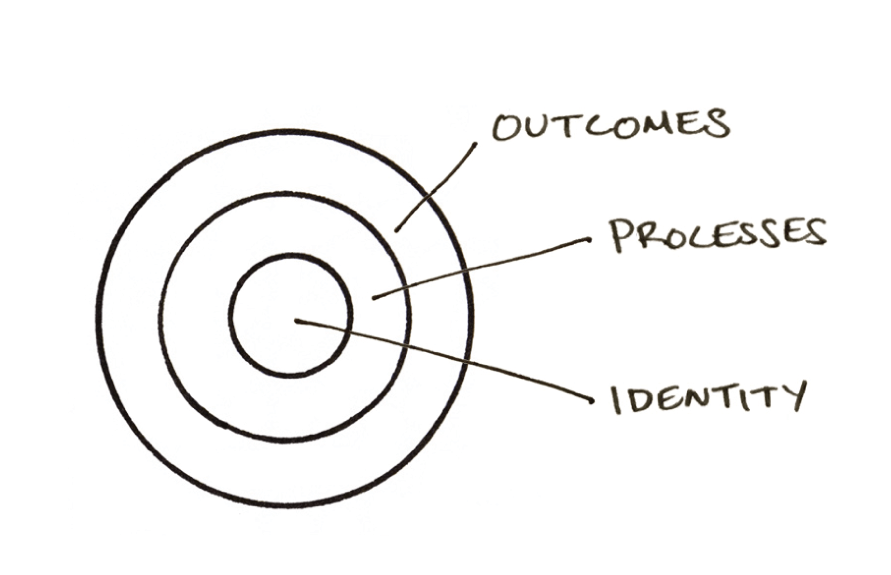

Most people start by focusing on outcome-based goals like “I want to lose 20 pounds” or “I want to write a best-selling book.”

But these are surface level changes.

The root of behavior change and building better habits is your identity. Each action you perform is driven by the fundamental belief that it is possible. So if you change your identity (the type of person that you believe that you are), then it’s easier to change your actions.

This brings us to an important question: How, exactly, is your identity formed? And how can you emphasize new aspects of your identity that serve you and gradually erase the pieces that hinder you?

How to Change Your Beliefs

Your identity emerges out of your habits. You are not born with preset beliefs. Every belief, including those about yourself, is learned and conditioned through experience. 1

More precisely, your habits are how you embody your identity. When you make your bed each day, you embody the identity of an organized person. When you write each day, you embody the identity of a creative person. When you train each day, you embody the identity of an athletic person.

The more you repeat a behavior, the more you reinforce the identity associated with that behavior. In fact, the word identity was originally derived from the Latin words essentitas, which means being, and, identidem, which means repeatedly. Your identity is literally your “repeated beingness.”

2Whatever your identity is right now, you only believe it because you have proof of it. If you go to church every Sunday for twenty years, you have evidence that you are religious. If you study biology for one hour every night, you have evidence that you are studious. If you go to the gym even when it’s snowing, you have evidence that you are committed to fitness. The more evidence you have for a belief, the more strongly you will believe it.

For most of my early life, I didn’t consider myself a writer. If you were to ask any of my high school teachers or college professors, they would tell you I was an average writer at best: certainly not a standout. When I began my writing career, I published a new article every Monday and Thursday for the first few years. As the evidence grew, so did my identity as a writer. I didn’t start out as a writer. I became one through my habits.

Of course, your habits are not the only actions that influence your identity, but by virtue of their frequency they are usually the most important ones. Each experience in life modifies your self-image, but it’s unlikely you would consider yourself a soccer player because you kicked a ball once or an artist because you scribbled a picture. As you repeat these actions, however, the evidence accumulates and your self-image begins to change. The effect of one-off experiences tends to fade away while effect of habits gets reinforced with time, which means your habits contribute most of the evidence that shapes your identity. In this way, the process of building habits is actually the process of becoming yourself.

This is a gradual evolution. We do not change by snapping our fingers and deciding to be someone entirely new. We change bit by bit, day by day, habit by habit.3 We are continually undergoing microevolutions of the self.

Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become. If you finish a book, then perhaps you are the type of person who likes reading. If you go to the gym, then perhaps you are the type of person who likes exercise. If you practice playing the guitar, perhaps you are the type of person who likes music. Each habit is like a suggestion: “Hey, maybe this is who I am.”

No single instance will transform your beliefs, but as the votes build up, so does the evidence of your new identity. This is one reason why meaningful change does not require radical change. Small habits can make a meaningful difference by providing evidence of a new identity. And if a change is meaningful, it actually is big. That’s the paradox of making small improvements.

Putting this all together, you can see that habits are the path to changing your identity. The most practical way to change who you are is to change what you do.

- Each time you write a page, you are a writer.

- Each time you practice the violin, you are a musician.

- Each time you start a workout, you are an athlete.

- Each time you encourage your employees, you are a leader.

Each habit not only gets results but also teaches you something far more important: to trust yourself. You start to believe you can actually accomplish these things. When the votes mount up and the evidence begins to change, the story you tell yourself begins to change as well.

Of course, it works the opposite way, too. Every time you choose to perform a bad habit, it’s a vote for that identity. The good news is that you don’t need to be perfect. In any election, there are going to be votes for both sides. You don’t need a unanimous vote to win an election; you just need a majority. It doesn’t matter if you cast a few votes for a bad behavior or an unproductive habit. Your goal is simply to win the majority of the time.

This is why I advocate starting with incredibly small actions (small votes still count!) and building consistency. Use the 2-Minute Rule to get started. Follow the Seinfeld Strategy to maintain consistency. Each action becomes a small vote that tells your mind, “Hey, I believe this about myself.” And at some point, you actually will believe it.

New identities require new evidence. If you keep casting the same votes you’ve always cast, you’re going to get the same results you’ve always had. If nothing changes, nothing is going to change.

This article is an excerpt from Chapter 2 of my New York Times bestselling book Atomic Habits. Read more here.

Certainly, there are some aspects of your identity that tend to remain unchanged over time—like identifying as someone who is tall or short. But even for more fixed qualities and characteristics, whether you view them in a positive or negative light is determined by your experiences throughout life.

Technically, identidem is a word belonging to the Late Latin language. Also, thanks to Tamar Shippony, a reader of jamesclear.com, who originally told me about the etymology of the word identity, which she looked up in the American Heritage Dictionary.

This is another reason atomic habits are such an effective form of change. If you change your identity too quickly and become someone radically different overnight, then you feel as if you lose your sense of self. But if you update and expand your identity gradually, you will find yourself reborn into someone totally new and yet still familiar. Slowly—habit by habit, vote by vote—you become accustomed to your new identity. Atomic habits and gradual change are the keys to identity change without identity loss.