The natural tendency of life is to find stability. In biology we refer to this process as equilibrium or homeostasis.

For example, consider your blood pressure. When it dips too low, your heart rate speeds up and nudges your blood pressure back into a healthy range. When it rises too high, your kidneys reduce the amount of fluid in the body by flushing out urine. All the while, your blood vessels help maintain the balance by contracting or expanding as needed.

The human body employs hundreds of feedback loops to keep your blood pressure, body temperature, glucose levels, calcium levels, and many other processes at a stable equilibrium.

In his book, Mastery, martial arts master George Leonard points out that our daily lives also develop their own levels of homeostasis. We fall into patterns for how often we do (or don't) exercise, how often we do (or don't) clean the dishes, how often we do (or don't) call our parents, and everything else in between. Over time, each of us settles into our own version of equilibrium.

Like your body, there are many forces and feedback loops that moderate the particular equilibrium of your habits. Your daily routines are governed by the delicate balance between your environment, your genetic potential, your tracking methods, and many other forces. As time goes on, this equilibrium becomes so normal that it becomes invisible. All of these forces are interacting each day, but we rarely notice how they shape our behaviors.

That is, until we try to make a change.

The Myth of Radical Change

The myth of radical change and overnight success is pervasive in our culture. Experts say things like, “The biggest mistake most people make in life is not setting goals high enough.” Or they tell us, “If you want massive results, then you have to take massive action.”

On the surface, these phrases sound inspiring. What we fail to realize, however, is that any quest for rapid growth contradicts every stabilizing force in our lives. Remember, the natural tendency of life is to find stability. Anytime equilibrium is lost, the system is motivated to restore it.

If you step too far outside the bounds of your normal performance, then nearly all of the forces in your life will be screaming to get you back to equilibrium. If you take massive action, then you quickly run into a massive roadblock.

Nearly anyone who has tried to make a big change in their life has experienced some form of this. You finally work up the motivation to stick with a new diet only to find your co-workers subtly undermining your efforts. You commit to going for a run each night and within a week you're asked to stay late at work. You start a new meditation habit and your kids keep barging into the room. 1

“Resistance is proportionate to the size and speed of the change, not to whether the change is a favorable or unfavorable one.”

The forces in our lives that have established our current equilibrium will work to pull us back whether we are trying to change for better or worse. In the words of George Leonard, “Resistance is proportionate to the size and speed of the change, not to whether the change is a favorable or unfavorable one.” 2

In other words, the faster you try to change, the more likely you are to backslide. The very pursuit of rapid change dials up a wide range of counteracting forces which are fighting to pull you back into your previous lifestyle. You might be able to beat equilibrium for a little while, but pretty soon your energy fades and the backsliding begins.

The Optimal Rate of Growth

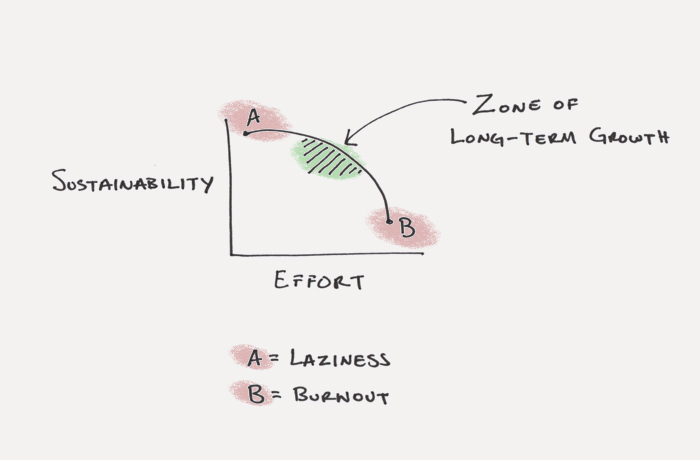

Of course, change is certainly possible, but it is only sustainable within a fairly narrow window. When an athlete trains too hard, she ends up sick or injured. When a company changes course too quickly, the culture breaks down and employees get burnt out. When a leader pushes his personal agenda to the extreme, the nation riots and the people re-establish the balance of power. Living systems do not like extreme conditions.

Thankfully, there is a better way.

Consider the following quote from systems expert Peter Senge. “Virtually all natural systems, from ecosystems to animals to organizations, have intrinsically optimal rates of growth. The optimal rate is far less than the fastest possible growth. When growth becomes excessive—as it does in cancer—the system itself will seek to compensate by slowing down; perhaps putting the organization's survival at risk in the process.” 3

By contrast, when you accumulate small wins and focus on one percent improvements, you nudge equilibrium forward. It is like building muscle. If the weight is too light, your muscles will atrophy. If the weight is too heavy, you'll end up injured. But if the weight is just a touch beyond your normal, then your muscles will adapt to the new stimulus and equilibrium will take a small step forward.

The Paradox of Behavior Change

In order for change to last, we must work with the fundamental forces in our lives, not against them. Nearly everything that makes up your daily life has an equilibrium—a natural set point, a normal pace, a typical rhythm. If we reach too far beyond this equilibrium, we will find ourselves being yanked back to the baseline.

Thus, the best way to achieve a new level of equilibrium is not with radical change, but through small wins each day.

This is the great paradox of behavior change. If you try to change your life all at once, you will quickly find yourself pulled back into the same patterns as before. But if you merely focus on changing your normal day, you will find your life changes naturally as a side effect.

It is worth noting that radical change can work, but only under very specific circumstances. Most notably, radical changes work when we are forced to accept them permanently. For example, people will often radically change their behavior after major life events like graduating college, moving to a new city, starting a new job, getting married, having a baby. (Pro tip: don't try all of those at once.) These big changes lead to entirely new habits that persist for years. Why? Because generally speaking, it's quite difficult to get rid of a baby, get divorced, find a new job, move to a new city, and so on. The new lifestyle is permanent and so are the radically new habits that come with it.

In his book Mastery, George Leonard shares an interesting insight about change and homeostasis. Leonard points out that stability is comfortable and that means, by default, change is uncomfortable. Thus, it is not always a bad thing to feel some pain or discomfort or uncertainty when trying something new (within reason) because these feelings can be seen as a signal not that something is wrong, but that something is right. You are experiencing discomfort precisely because you are changing.

The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge. Page 62.