This article is an excerpt from Atomic Habits, my New York Times bestselling book.

In 2007, researchers at Oxford University started peering into the brains of newborn babies. What they found was surprising.

After comparing the newborn brains to the normal adult human, the researchers realized that the average adult had 41 percent fewer neurons than the average newborn. 1

At first glance, this discovery didn't make sense. If babies have more neurons, then why are adults smarter and more skilled?

Let's talk about what is going on here, why this is important, and what it has to do with building better habits and mastering your mental and physical performance.

The Power of Synaptic Pruning

There is a phenomenon that happens as we age called synaptic pruning. Synapses are connections between the neurons in your brain. The basic idea is that your brain prunes away connections between neurons that don't get used and builds up connections that get used more frequently.

For example, if you practice playing the piano for 10 years, then your brain will strengthen the connections between those musical neurons. The more you play, the stronger the connections become. Not only that, the connections become faster and more efficient each time you practice. As your brain builds stronger and faster connections between neurons, you can express your skills with more ease and expertise. It is a biological change that leads to skill development.

Meanwhile, someone else who has never played the piano is not strengthening those connections in their brain. As a result, the brain prunes away those unused connections and allocates energy toward building connections for other life skills.

This explains the difference between newborn brains and adult brains. Babies are born with brains that are like a blank canvas. Everything is a possibility, but they don't have strong connections anywhere. The adults, however, have pruned away a good deal of their neurons, but they have very strong connections that support certain skills.

Now for the fun part. Let's talk about how synaptic pruning plays an important role in building new habits.

Habit Stacking

Synaptic pruning occurs with every habit you build. As we've covered, your brain builds a strong network of neurons to support your current behaviors. The more you do something, the stronger and more efficient the connection becomes.

You probably have very strong habits and connections that you take for granted each day. For example, your brain is probably very efficient at remembering to take a shower each morning or to brew your morning cup of coffee or to open the blinds when the sun rises … or thousands of other daily habits. You can take advantage of these strong connections to build new habits.

How?

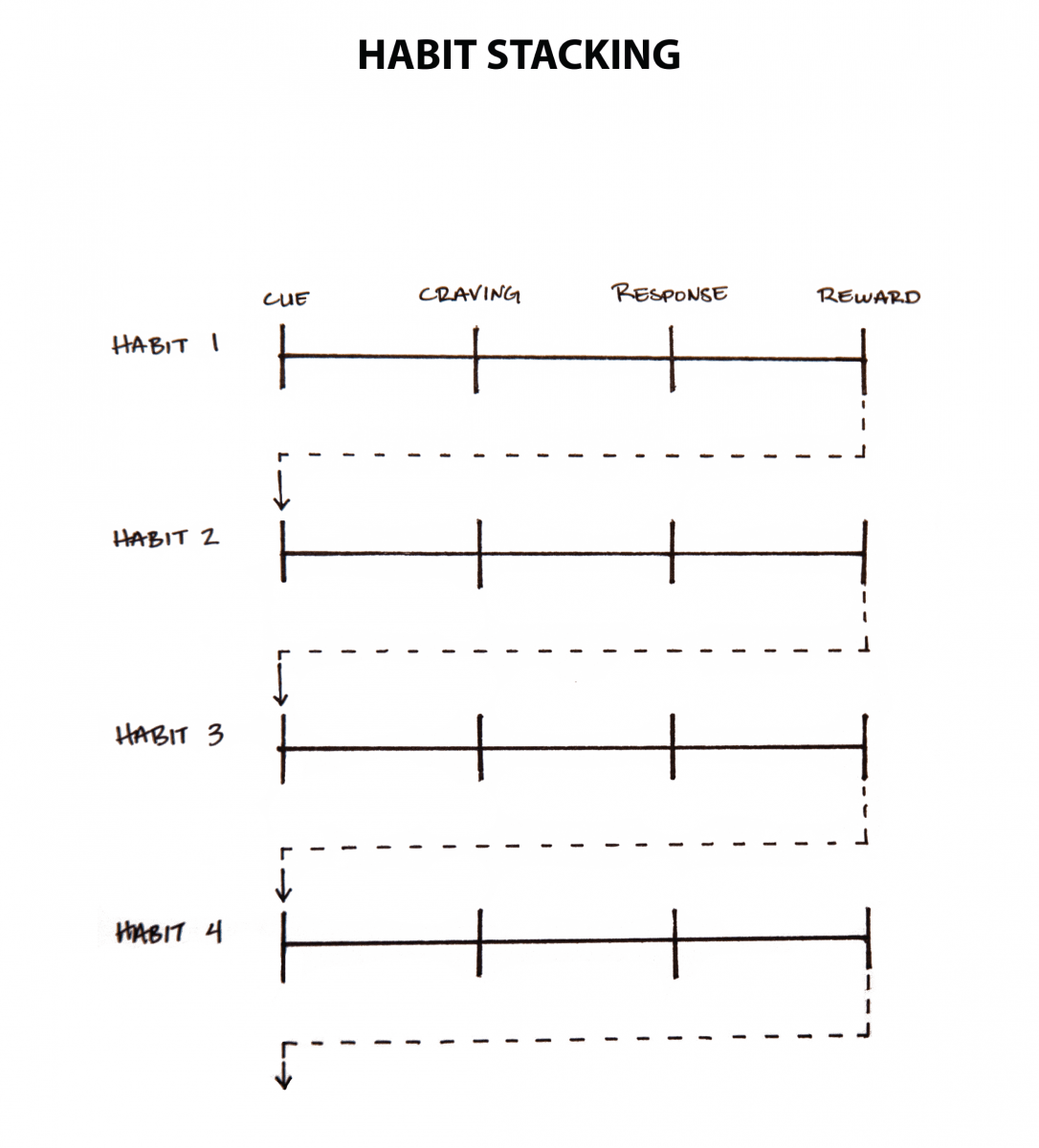

When it comes to building new habits, you can use the connectedness of behavior to your advantage. One of the best ways to build a new habit is to identify a current habit you already do each day and then stack your new behavior on top. This is called habit stacking.

Habit stacking is a special form of an implementation intention. Rather than pairing your new habit with a particular time and location, you pair it with a current habit. This method, which was created by BJ Fogg as part of his Tiny Habits program,2 can be used to design an obvious cue for nearly any habit.

Habit Stacking Examples

The habit stacking formula is:

After/Before [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].

For example:

- After I pour my cup of coffee each morning, I will meditate for one minute.

- After I take off my work shoes, I will immediately change into my workout clothes.

- After I sit down to dinner, I will say one thing I’m grateful for that happened today.

- After I get into bed at night, I will give my partner a kiss.

- After I put on my running shoes, I will text a friend or family member where I am running and how long it will take.

Again, the reason habit stacking works so well is that your current habits are already built into your brain. You have patterns and behaviors that have been strengthened over years. By linking your new habits to a cycle that is already built into your brain, you make it more likely that you'll stick to the new behavior.

Once you have mastered this basic structure, you can begin to create larger stacks by chaining small habits together. This allows you to take advantage of the natural momentum that comes from one behavior leading into the next.

Your morning routine habit stack might look like this:

- After I pour my morning cup of coffee, I will meditate for sixty seconds.

- After I meditate for sixty seconds, I will write my to-do list for the day.

- After I write my to-do list for the day, I will immediately begin my first task.

Or, consider this habit stack in the evening:

- After I finish eating dinner, I will put my plate directly into the dishwasher.

- After I put my dishes away, I will immediately wipe down the counter.

- After I wipe down the counter, I will set out my coffee mug for tomorrow morning.

You can also insert new behaviors into the middle of your current routines. For example, you may already have a morning routine that looks like this: Wake up > Make my bed > Take a shower. Let’s say you want to develop the habit of reading more each night. You can expand your habit stack and try something like: Wake up > Make my bed > Place a book on my pillow > Take a shower. Now, when you climb into bed each night, a book will be sitting there waiting for you to enjoy.

Overall, habit stacking allows you to create a set of simple rules that guide your future behavior. It’s like you always have a game plan for which action should come next. Once you get comfortable with this approach, you can develop general habit stacks to guide you whenever the situation is appropriate:

- When I see a set of stairs, I will take them instead of using the elevator.

- Social skills. When I walk into a party, I will introduce myself to anyone I don’t know yet.

- When I want to buy something over $100, I will wait 24 hours before purchasing.

- Healthy eating. When I serve myself a meal, I will always put veggies on my plate first.

- When I buy a new item, I will give something away. (“One in, one out.”)3

- When the phone rings, I will take one deep breath and smile before answering.

- When I leave a public place, I will check the table and chairs to make sure I don’t leave anything behind.

No matter how you use this strategy, the secret to creating a successful habit stack is selecting the right cue to kick things off. Unlike an implementation intention, which specifically states the time and location for a given behavior, habit stacking implicitly has the time and location built into it. When and where you choose to insert a habit into your daily routine can make a big difference. If you’re trying to add meditation into your morning routine but mornings are chaotic and your kids keep running into the room, then that may be the wrong place and time. Consider when you are most likely to be successful. Don’t ask yourself to do a habit when you’re likely to be occupied with something else.

Your cue should also have the same frequency as your desired habit. If you want to do a habit every day, but you stack it on top of a habit that only happens on Mondays, that’s not a good choice.

Finding the Right Trigger

One way to find the right trigger for your habit stack is by brainstorming a list of your current habits. You can use your Habits Scorecard as a starting point. Alternatively, you can create a list with two columns. In the first column, write down the habits you do each day without fail.

For example:

- Get out of bed.

- Take a shower.

- Brush your teeth.

- Get dressed.

- Brew a cup of coffee.

- Eat breakfast.

- Take the kids to school.

- Start the work day.

- Eat lunch.

- End the work day.

- Change out of work clothes.

- Sit down for dinner.

- Turn off the lights.

- Get into bed.

Your list can be much longer, but you get the idea. In the second column, write down all of the things that happen to you each day without fail. For example:

- The sun rises.

- You get a text message.

- The song you are listening to ends.

- The sun sets.

Armed with these two lists, you can begin searching for the best place to layer your new habit into your lifestyle.

The Next Step

Habit stacking works best when the cue is highly specific and immediately actionable. Many people select cues that are too vague. I made this mistake myself. When I wanted to start a push-up habit, my habit stack was, “When I take a break for lunch, I will do ten push-ups.” At first glance, this sounded reasonable. But soon, I realized the trigger was unclear. Would I do my push-ups before I ate lunch? After I ate lunch? Where would I do them? After a few inconsistent days, I changed my habit stack to: “When I close my laptop for lunch, I will do ten push-ups next to my desk.” Ambiguity gone.

Habits like “read more” or “eat better” are worthy causes but far too vague. These goals do not provide instruction on how and when to act. Be specific and clear: After I close the door. After I brush my teeth. After I sit down at the table. The specificity is important. The more tightly bound your new habit is to a specific cue, the better the odds are that you will notice when the time comes to act.

Happy habit stacking!4

This article is an excerpt from Chapter 4 of my New York Times bestselling book Atomic Habits. Read more here.

Excess of Neurons in the Human Newborn Mediodorsal Thalamus Compared with That of the Adult by Maja Abitz, Rune Damgaard Nielsen, Edward G. Jones, Henning Laursen, Niels Graem and Bente Pakkenberg

I use the term habit stacking to refer to linking a new habit to an old one. For this idea, I give credit to BJ Fogg. In his work, Fogg uses the term anchoring to describe this approach because your old habit acts as an “anchor” that keeps the new one in place. No matter what term you prefer, I believe it is a very effective strategy. You can learn more about Fogg’s work and his Tiny Habits Method at https://www.tinyhabits.com/

Dev Basu (@devbasu), “Have a one-in-one-out policy when buying things,” Twitter, February 11, 2018.

Thanks to SJ Scott for inspiring me to use the word “habit stacking” from his book by that name. I haven't read it, but I like the phrase!