In many cases, improvement is not about doing more things right, but about doing less things wrong.

To understand what I mean, we need to take a trip to Japan.

The Curious Case of Japanese Television Sets

In the decades that followed World War II, the manufacturing industry in America thrived. For years, American companies grew in size and profitability—even though they produced many products of average quality.

This gravy train began to slide off the tracks in the 1970s. Japanese firms implemented a series of surprising changes that helped them crush their American counterparts. As one New Yorker article put it…

“Japanese firms emphasized what came to be known as “lean production,” relentlessly looking to remove waste of all kinds from the production process, down to redesigning workspaces, so workers didn’t have to waste time twisting and turning to reach their tools. The result was that Japanese factories were more efficient and Japanese products were more reliable than American ones. In 1974, service calls for American-made color televisions were five times as common as for Japanese televisions. By 1979, it took American workers three times as long to assemble their sets.” 1

Business buzzwords like Kaizen, Lean Production, and Process Improvement are so ubiquitous today that it can be easy to gloss over the subtlety of the Japanese strategy.

The key insight I'd like to point out here is the difference between focusing on getting better vs. not getting worse. Japanese television makers did not seek out more intelligent workers or better materials, they simply said, “Let's build the same product, but make fewer mistakes.” Japanese companies improved by subtracting the things that didn't work, not by creating a bigger, better, or more expansive product.

This is an important distinction and it applies to habits, processes, and goals of all kinds, not just television sets.

Two Paths to Process Improvement

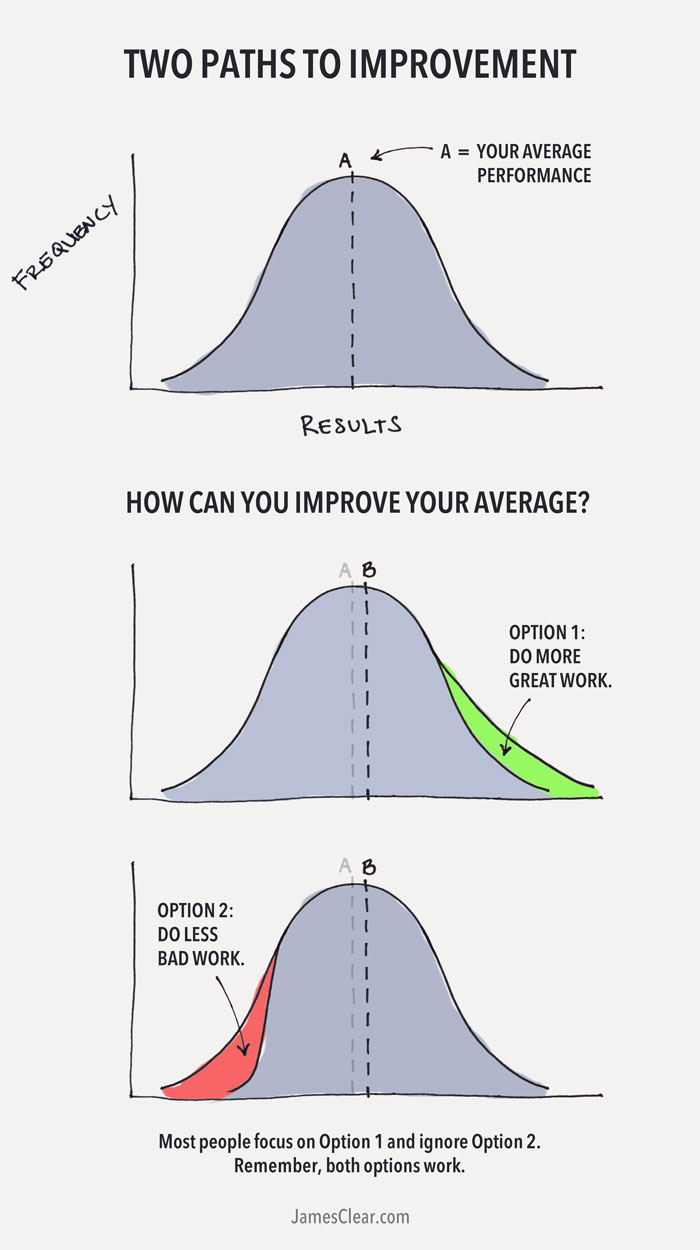

The distinction we are making here is between improvement by addition vs. improvement by subtraction. Improvement by addition is focused on doing more of what does work: producing a faster car, creating a more powerful speaker, building a stronger table. Improvement by subtraction is focused on doing less of what doesn't work: eliminating mistakes, reducing complexity, and stripping away the inessential.

These concepts of addition and subtraction apply to many areas of life.

Education

- Addition: become more intelligent, increase your IQ.

- Subtraction: avoid stupid mistakes, make fewer mental errors.

Investing

- Addition: earn more money, seek growth opportunities.

- Subtraction: never lose money, limit your risk.

Web Design

- Addition: improve your call-to-action copy, boost conversions.

- Subtraction: remove the on-page elements that distract visitors.

Baseball

- Addition: get more hits.

- Subtraction: make fewer outs.

Exercise

- Addition: make your workouts more intense.

- Subtraction: miss fewer workouts.

Nutrition

- Addition: follow a new diet of healthy foods.

- Subtraction: eat fewer unhealthy foods.

Many of these approaches seem similar, but they are not the same. Take the nutrition example above. Eating healthy foods and avoiding unhealthy foods seems very similar. However, in the first case, your focus is on “how to eat better” whereas the second case is focused on “how to not eat worse.” In one scenario you are trying to chase the upside, in another you are focused on limiting the downside.

Improvement by Subtraction

Nearly every manager in the world wants to “do more great work”, but very few people want to “do less bad work.” We love peak performances. Every athlete wants to play an amazing game. Every business owner wants to land a blockbuster sale. Every writer wants to launch a best-selling book. Our desire for that next level of performance causes us to disproportionately focus on the front end of the curve.

Eliminating mistakes is an underappreciated way to improve. In the real world, it is often easier to improve your performance by cutting the downside rather than capturing the upside. Subtraction is more practical than addition. This is true for two reasons.

First, it is often easier to eliminate errors than it is to master peak performance. By simply writing down every step of a process, you can often identify a few areas that can be reduced or eliminated altogether. The easiest improvements I have made to my website were a result of eliminating every inessential element.

Second, improvement by subtraction does not require you to achieve a new level of performance. This method is about doing what you are capable of doing more frequently. It is about reducing the likelihood that you'll perform below your ability.

One of the best ways to make big gains is to avoid tiny losses.2

“Better All the Time” by James Surowiecki. November 10, 2014.

Thanks to readers Jim and Andrius for recommending the New Yorker article and to Shane Parrish for priming my thoughts on this topic by writing about why “avoiding stupidity is easier than seeking brilliance.”